Making sense when nothing makes sense

The meaning of meaning is a question that has been keeping philosophers and linguists awake at night for a long, long time, and which keeps me awake at night.

I am a computational semanticist. Semantics is the study of meaning. My job, computational semantics, is to study meaning by producing computer simulations of all the different ways humans make sense of sentences, words, situations, of what exists (the real world) and of what does not exist (what I will call ‘possible worlds’).

It may come as a surprise to you that I don’t know what it is that I study. I am supposed to dissect meaning, but I am not sure what meaning is. In my defense, that is perhaps no different from what happens in other disciplines. Physicists, for instance, debate about the nature of time. Biologists debate about the nature of life. We semanticists debate about the nature of meaning.

There are of course various linguistic theories of meaning, which highlight different aspects of humans’ thirst for ‘making sense’. The scientific concepts that have been explored over the years can be helpful to all of us, right now, when thinking about our place in what is often a very confusing world.

I should point out that those theories are somewhat at odds with each other in the scientific literature, and correspond to different ‘camps’ holding sometimes incompatible view points. There is much work to be done to reconcile them – if they are reconciliable at all. However, my personal stance as a scientist is that each of them holds important insights about our relation to meaning, and that together, they convey a precious narrative about one of the most fundamental aspects of the mind.

So in this post, we will discuss the notions of grammar and acceptability, and how we human beings, always strive to find meaning, even in what might appear senseless. We will inspect the notion of meaning with respect to possible worlds – what is not here and now but that our minds can nevertheless conceptualise – and we will see how those possible worlds naturally model the sheer heterogeneity and dynamicity of meaning, allowing us to go beyond what we thought we knew and believed. Finally, we will see that meaning is not something that things have, but something that we do, collectively. And I will conclude that especially in times of crisis, we must trust our ability to do meaning, our ability to MAKE sense.

Meaning and grammar

Let us start rather unconventionally, with a strand of research which is actually not so invested in meaning: the Chomskian linguistic tradition. The reasons why this tradition has kept meaning at bay are interesting, and they will give us a good departure point to understand what it is that we are talking about.

When you think about what a linguist does, you may think of your grammar lessons at school. Regardless of your mother tongue, you will probably have learned rules that tell you, for instance, how to combine a subject and a verb together. In English, the sentence She sleeps is syntactically correct: we are combining a third person singular subject with a third person singular verb. But the sentence She sleep is incorrect: here, we have tried to combine a singular subject with a plural verb. Similarly, the sentence She slept in a tent is correct (you can build the syntactic structure of that sentence), but She slept a tent is not (there is no possible syntactic tree for that sentence).

Back in the 1960s, philosophers Jerrold Katz and Jerry Fodor proposed that one could talk about meaning in terms of grammar. They were following insights by linguist Noam Chomsky on the structure of syntax.

Katz and Fodor were interested in finding out what semantics brings to syntax in terms of understanding and correctness. They wanted to model disambiguation and acceptability. For instance, they wanted to show that a sentence such as The bill is large, which only has one syntactic interpretation, actually has different semantic interpretations depending on whether we talk about a restaurant’s bill, or a bird’s bill. They also wanted to explain why sentences such as The paint is silent seem nonsensical.

The consequence of Katz and Fodor’s work is that there is a strong notion of grammaticality associated with meaning: there are things you can say and things you can’t say (meaningfully). Some things make sense, others don’t. Chomsky himself illustrated this with the famous sentence Colorless green ideas sleep furiously, which according to him is syntactically correct but semantically non-sensical.

The problem is that people love making sense of the colorless green ideas. There was a competition in Stanford in 1985, asking people to write a little paragraph or poem interpreting that sentence. Students rose to the challenge, coming up with metaphorical contexts which gave sense to the utterance. And many linguists have their own favourite interpretation of the sentence.

So a better analysis of the phenomenon might be to say that some things are harder to make sense of than others. Psycholinguists can detect the difficulty of a sentence by performing eye-tracking experiments on human participants, which measure how long it takes to read a particular chunk of text. There is no question that the sentence Colorless green ideas sleep furiously might require longer reading time than the sentence The green party is furiously against that idea. But saying this is not the same as saying that people do not or cannot search for sense in it. If we were not able to look for structure and patterns in the world around us, we would miss out on many things that make us humans: we would be very impoverished learners, we would be bad scientists, and we would be unable to engage in basic social behaviours such as ‘putting oneself in another person’s shoes’. Trying to decipher something that does not make direct sense to us is a fundamental human ability.

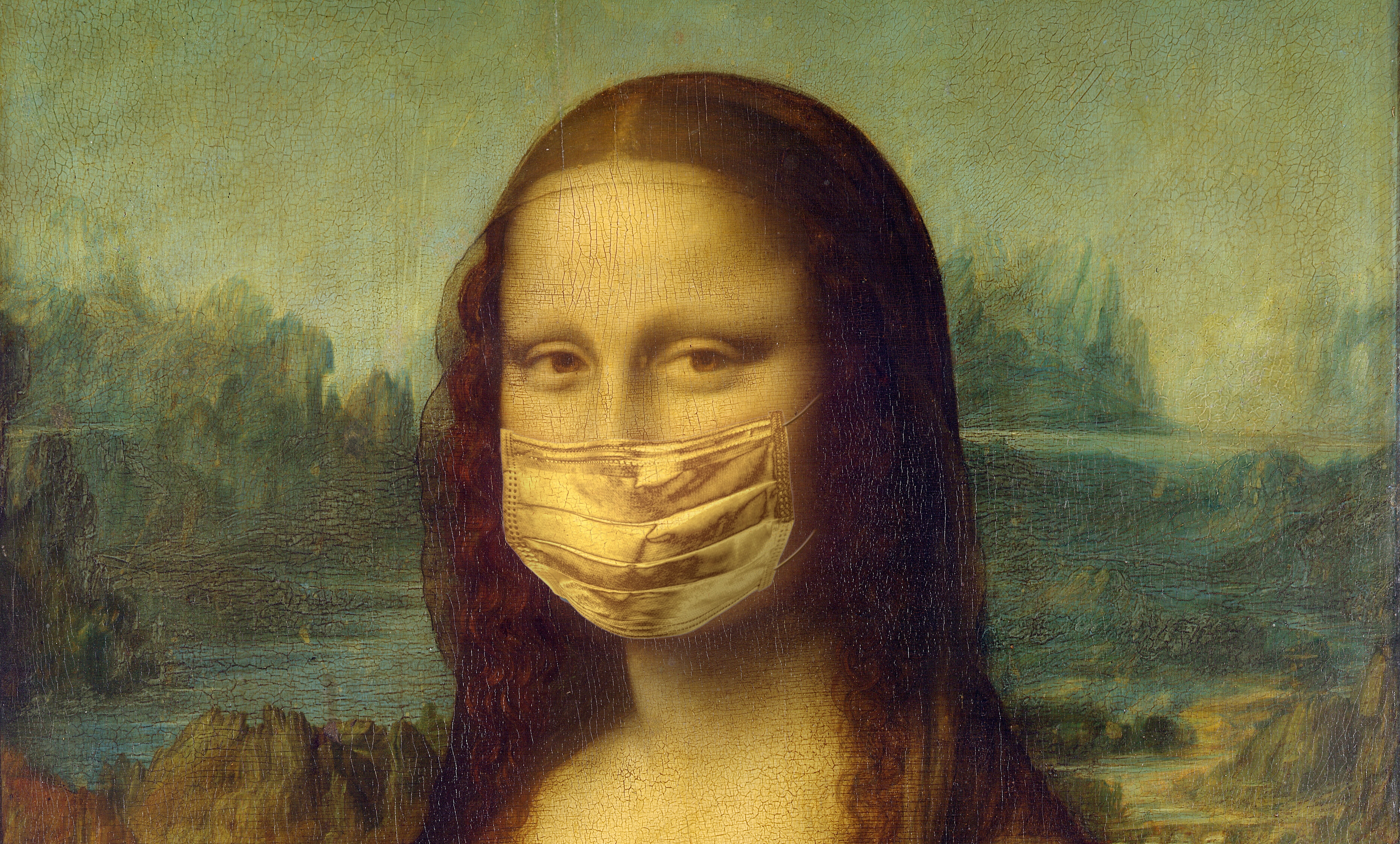

When the world around us seems strange, our human minds still desperately try to make sense of it. And it is hard and confusing because the situation seems to be breaking the very grammar of the world we thought we lived in. Remember the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the adaptations it required of us. Just like a singular subject wants to agree with a singular verb, isn’t it that going to work goes with going out of your house, that greeting someone goes with shaking hands, hugging, kissing? We recognise the structure of the languages we speak because we share a grammar with others. We recognise the structure of the world because we share practices with others. So when ungrammaticality appears, when greeting someone becomes a physical distancing affair, we initially find it very hard to comprehend.

A pessimistic assessment of this state of affairs would state that trying to make sense of things, however senseless they are, is an unfortunate human trait. Wouldn’t it be easier to just throw in the towel and say ‘this doesn’t make sense’ when things do not make sense? Wait for better days in times of crisis? Is there ever a point in trying to rescue a broken grammar?

Meaning and worlds

Coming from philosophy, another view of meaning is that it links language and the world in some kind of correspondence. Philosopher Alfred Tarski put it simply by writing “The sentence ‘snow is white’ is true if and only if snow is white”.

Logician Richard Montague took this insight and showed that the syntax of language could be mapped onto a logic that can link bits of sentences with bits of the world, and tell whether a sentence is true or false. The sentence The cat sleeps is true if, in the world, there is a thing which I could call a cat, an event which I could refer to as ‘sleeping’, and if it is the cat does that the sleeping. This tradition is called ‘Formal Semantics’.

On the back of this theory, you may think that making sense is about truth. This is not so, at least not in the conventional sense of ‘truth’. As linguist Barbara Partee reminds us, “semantics itself is in the first instance concerned with truth-conditions (not actual truth, as is sometimes mistakenly asserted)”. To me, this is a fundamental and perhaps overlooked aspect of formal semantics. Montague posits that meaning is related not to the world, but to an infinity of possible worlds, interpreted according to particular contexts of use. That is, my interpretation of The cat sleeps today at 9:30pm in Northern Italy may be different from yours, reading the same sentence tomorrow at 5am in Kenya. Truth in the formal sense – the way we attach words to things in some world – is relative.

What falls out of this is that the notion of acceptability is much blurrier than grammarians would have it. With a logical notion of possible worlds, you can make any utterance true by picking the right world. In that way, even sleeping ideas get a meaning. I usually explain this in class by drawing on the board a set of cute sleeping animals and a set of ideas, represented by lightbulbs. Finding a world in which you have sleeping ideas is as simple as ‘intersecting’ the two sets. I draw sleepy eyes on some of the lightbulbs, and there you have it, here is a world with sleeping ideas. Of course, the world you have to pick to make this work may be very remote from reality. It may be hard to relate to or conceptualise. But the point is that formally, meaning has not disappeared. The mechanism that makes you attach words to things is still there, however ridiculous your possible worlds might be.

Relative truth may sound scary. Isn’t that what we are trying to fight in our modern societies? Fake news, widespread lies, unfounded, pseudo-scientific, dangerous political theories? This is not what the formal notion of truth is about, though. There is of course a real world, and there are claims that are verifiable in the real world, and others which are not. But the real world is dynamic, and so are we. The world of yesterday is not the world of today. What we were doing yesterday is not what we are doing today. The fears and hopes we had yesterday (our possible worlds) are not the ones we have today. Utterances that would have made little sense yesterday make sense today. Many utterances that still do not make sense might just be looking for a world in which they can live.

Meaning and doing

Somewhat in contrast with formal semantics, another strand of research rejects correspondence theory and advocates the notion of “meaning as use”. This notion comes from the later work of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. It departs from traditional philosophical approaches where a word or sentence gets its sense from something that is external to it (for instance, in the formal semantics tradition, a world, or a mental representation of a world). For Wittgenstein, the meaning of a word is as diverse as all its contexts of utterance, and there is not much point in trying to give it a definition. Instead, we must observe similarities and overlaps in the actual utterances of speakers.

There is an interesting historical link between Wittgenstein and modern computational semantics. Wittgenstein had a student called Margaret Masterman. Masterman was very influenced by Wittgenstein’s ideas on meaning, and she also believed that they could be experimentally tested with a brand new tool: the computer. In 1955, she founded the Cambridge Language Research Unit, which did early work in computational linguistics. Of relevance to us, one of the members of the Cambridge Language Research Unit, Karen Spärck-Jones, would perform seminal experiments in what today, my field of research calls distributional semantics.

What is distributional semantics? Paraphrasing Wittgenstein, the idea that meaning emerges from language use and its context. Computationally, it means that by feeding a system with raw language data, sometimes associated with images and sounds, you can make it learn the conventional meaning of words and their combination. For instance, that ‘cat’ is more similar to ‘dog’ than to ‘stone’. That the words ‘financial’ and ‘bank’ put together have nothing to do with water (even though ‘bank’ on its own might…)

Distributional semantics models meaning as points in a space. To understand this, imagine that the three dimensions around you now contain little points floating around, and imagine that each one of those little points is the meaning of a word, a phrase or a sentence. Here is ‘cat’, with ‘dog’ next to it, and there is ‘I am hungry’, hanging in mid-air. Now, imagine that you live not in a 3-dimensional space, but in a space of hundreds of dimensions. And you have a semantic, or conceptual space. The position of the points in, say, an English space is directly related to the way that speakers of English have used English until now. If suddenly, for some reason, the word ‘dog’ was primarily used to talk about washing machines, then ‘dog’ would not float anymore next to ‘cat’ in that space. In other words, meaning emerges in space, from language use. It is created by what people do with their language.

The beauty of distributional semantics is that it shows the dynamicity of meaning. Combine the points of ‘financial’ and ‘bank’ together, and ‘bank’ will move through space to go and sit a little closer to ‘money’. Combine ‘river’ and ‘bank’, and ‘bank’ will jump closer to ‘water’. Say something, think something in words, and you send the whole space vibrating a little, ever so slightly changing the way things were. That space is not just space. It is time too. Some colleagues in my field study diachronic semantic change using distributional semantics. Their models show how meaning in a given language changes across time, as a function of what a community utters.

Distributional semantics is not very good at what formal semantics does best: relating words and worlds. However, it is a very clear model of the way every single of our linguistic actions – saying, hearing, writing, reading, thinking – contributes to ‘making sense’ in the most literal way.

‘Making sense’ is exactly that: making (sense). Sense has to be painstakingly constructed and reconstructed every time it crumbles. And as human beings, we are endowed with the mysterious cognitive mechanism that lets us build meaning, as naturally as we breathe: language. If we accept that language is not simply grammar, that with cognitive effort on our part, we also have the ability to look at other worlds, in the way that formal semantics allows us to do, we can make meanings emerge where there were none before.

For the record, Margaret Masterman, the founder of the Cambridge Language Research Unit, is also known for challenging the notion of a ‘paradigm’ in the famous work of Thomas Kuhn, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions”. She gives an interpretation of Kuhn distinguishing the rule-following science operating within a scientific paradigm, and the ‘intuitive’, non-rule-following steps which will form the foundation for a new scientific approach when the current one is in crisis. The point is that when a world view breaks, the rules, the grammar of that world must be replaced. The best tool we have to find a replacement is our ability to find patterns beyond the rules, to try out crude analogies and inexact inferences which may or may not survive, in a word, shake our conceptual spaces.

What to take from this?

Whenever the world is in crisis, some optimistic voices raise to tell us that we now have an opportunity to transform ourselves collectively. That by observing our shared condition synchronously, we get the chance to ask: could we wake up from this better people? Better to ourselves, to others, and to the world around us?

This sounds like a nice idea in principle, but there is nothing harder than inventing the future. Especially at a time when we might be fearful, sick or alone. So is the idea of collective transformation just an exaggerated idea invented by a few individuals who are (or feel) stronger than most of us are?

Perhaps not, if you look at things with the eyes of a linguist.

Calling upon grammar, I remember that meaning sometimes breaks the rules, betraying acceptability, literally making it unacceptable to me.

I also remember that no matter how unacceptable the proposition thrown at me by the current situation, I will want to make sense. Because I am human. And despite my natural tendency to want to remain within the grammar that I know, the rules that I have been trained to comply with.

Calling upon formal semantics, I remember that meaning is dynamic, that there is no absolute, eternal truth. That the real world I was measuring my thoughts against just yesterday is not anymore the real world. And that there is no reason for my possible worlds from yesterday – including my expectations and dreams – to be the possible worlds of today. Everything is always in a state of change.

Calling upon distributional semantics, I remember that making sense is a generative process. We, all together, will have to bring about new meanings, new truths, restore acceptability by using language, sharing language, creating common worlds with common words.

So perhaps we should tell. It is not clear what, or how. But we should tell, and we should tell it new. Tell how things are and how we are now. Not with the words we feel expected to use, the words of yesterday. But with the only words that seem to fit, however strange and ungrammatical they may seem to yesterday’s beliefs.

We don’t have to get over ourselves and pretend not to be scared, tired, or sad in times of crisis. We just have to collectively babble, and crucially, to trust that it is okay now to say the things we never said before. To trust that by saying them all together we are not only visiting our shared possible worlds but literally creating them as we speak. To trust, finally, that we cannot but MAKE sense. That it is the thing we most naturally do.